Natalie Chanin

From the pages of Vogue to an art gallery in Inman Park, Alabama fashion designer Natalie Chanin drops in to town to share her philosophy on the art of “Slow Design”

TAILORED STYLE

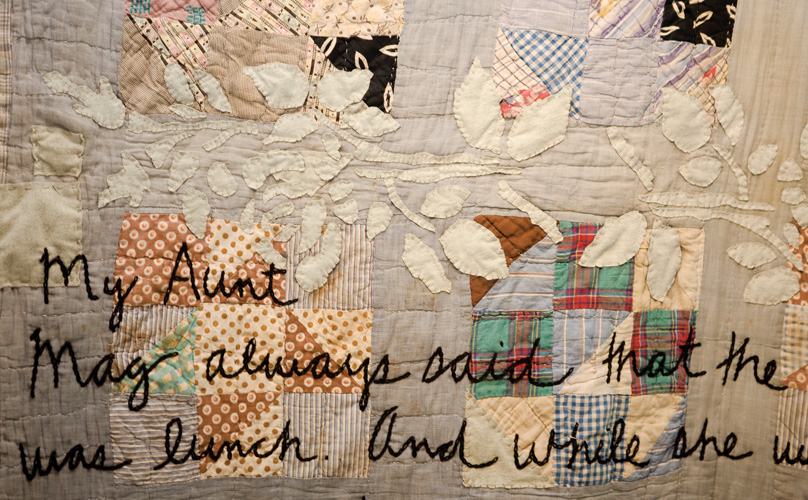

Fashion designer Natalie Chanin subscribes to a “by hand” school of thought. So it wasn’t surprising when, a few years ago, she moved her emerging design business from New York to her hometown of Florence, Alabama. Her label, “Alabama Chanin,” features clothing made from comfortable knit jersey—sometimes recycled and reclaimed, sometimes constructed of new, organic cotton. And while the fabric is simple and familiar, the stitching technique is most definitely not. Inspired by everything from quilts and nature to poetry and history, Chanin fuses a country aesthetic with a certain modern vibe

It was more than the tug of hometown heartstrings that made Northwest Alabama—known as “the Shoals” to the locals—perfectly suited to Chanin’s work. Once known for its textiles, stitchers made good livings there until, eventually, all the textile work moved overseas. Chanin needed to find folks who remembered the beauty and value in a hand-stitched garment and figured that those who were not that far removed from the quilting bee might be right in her own backyard. She was right.

Each piece of Alabama Chanin clothing is completely hand-stitched by folks who live in the Shoals. That, combined with her fabric choices and her decision to keep the business close to home, has led to Chanin being heralded as a pioneer in the “slow design” movement (the design version of “slow food”). Magazines such as Vogue and Vanity Fair, both of which have profiled her, seem to agree.

But the designer doesn’t limit herself to apparel. Alabama Chanin offers a variety of items for the home, including homespun-looking chairs, innovative lighting, unique pillows and—of course—breathtaking quilts. All have one thing in common, though: The hand-crafted pieces are signed by the artisans that made them.

Chanin tends to nourish herself by collaborating. Her web site and blog cite books and magazines that she has been reading, act as a forum for Mississippi writer and poet Blair Hobbs, and even reveal the designer’s favorite recipes.

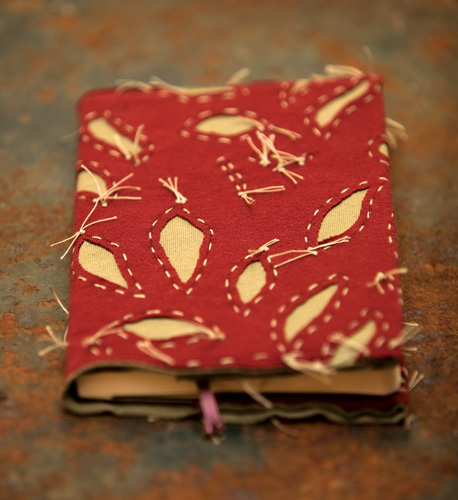

Her across-the-board success is due, in part, to the fact that Chanin sees the connections among sewing, cooking, writing, building, architecture—all of it. That, along with her desire to show people how they can create some of her designs at home, spawned the Alabama Stitch Book, published by Stewart, Tabori & Chang (2008). Featuring patterns, instructions and inspiration for projects from simple to ambitious, the book brings her philosophy full circle by encouraging others to join her in making things “by hand.”

Susan Bridges, owner of Inman Park’s Whitespace Gallery, recently invited fashion designer Natalie Chanin to Atlanta to show some of her Alabama Chanin quilts and host a one-day stitching workshop. Fifteen women, from diverse backgrounds, filled the renovated carriage house to stitch, share and eat.

While the women gathered at Whitespace learned Chanin’s reverse appliqué technique, the conversation revealed their varied backgrounds—among them, a contemporary photographer, a statistician for the CDC, a mother, a teenager and even a child. The talk shifted to favorite meals and recipes, then to deeper stories of family and home.

The day’s menu consisted of Southern standards like pimento cheese, barbecued chicken and pulled pork. A succotash made from butter beans, corn and squash was served along with the story of “the three sisters”—a Native American tale that personifies the vegetables, reminding us that those “three sisters,” when planted together, provide different nutrients to the soil and, because they can be consumed in both fresh and dried states, can provide nourishment all year long. Late-harvest tomatoes provided color to the table and, as a fitting final touch, homemade butterscotch pudding was poured into small jelly jars and topped with fresh whipped cream.

But more than eating and stitching happened around those tables that day. Stories were swapped, advice was given and—under the shelter of Bridges’ Whitespace—food and clothing were transformed into art forms.